[ad_1]

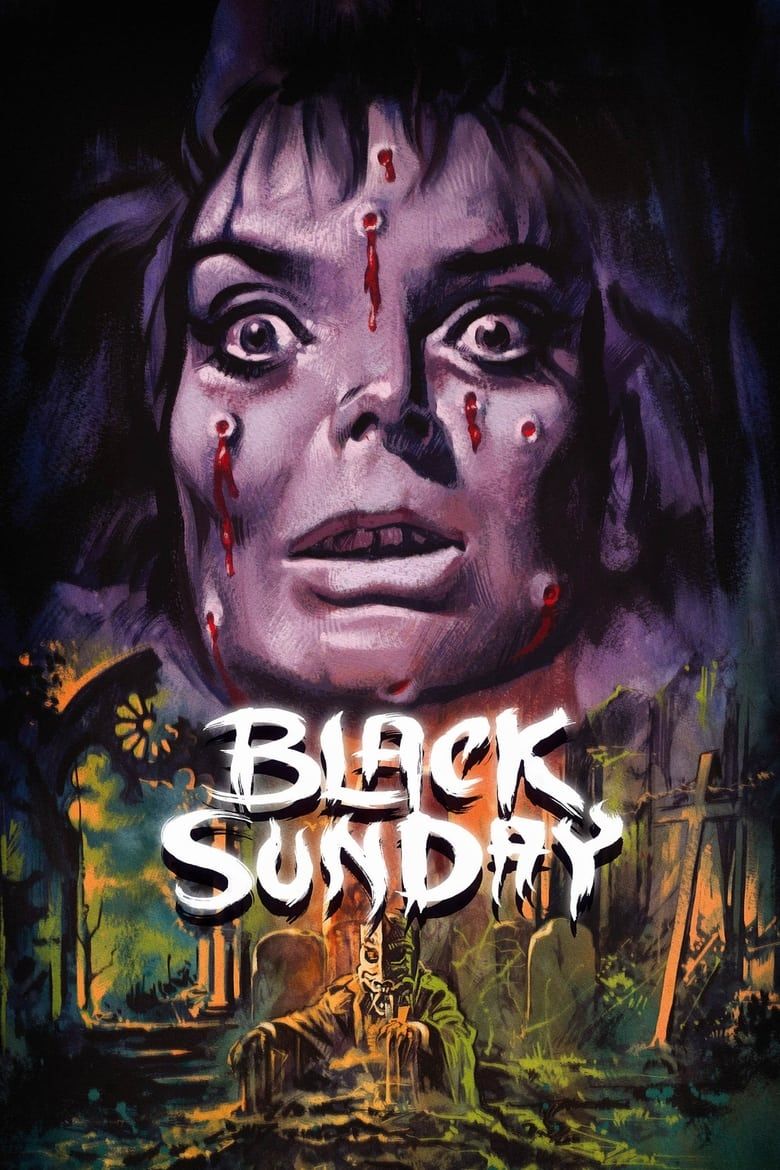

As hard as it is to imagine now, in the late ’50s—early ’60s, Italian cinema barely had a horror tradition to speak of. That is until a bunch of genre enthusiasts, inspired by Alfred Hitchcock‘s thrillers and the Hammer studio outings, basically invented one, having come up with a concept of a national tradition of horror that is both aesthetically stunning and wonderfully decadent. But before such titans of the European macabre as Dario Argento and Lucio Fulci fully came into their respective styles, the trailblazer who paved the way for many of his colleagues was Mario Bava, who was already a prominent cinematographer and special effects artist but was yet to make his directorial debut at the time. His first foray into directing came in 1960 with Black Sunday—a dark and sensual Gothic horror in which Bava managed to introduce major elements of not only his future trademark style, but also of the whole Italian horror tradition that would become a great source of inspiration for the genre auteurs around the world.

What Is ‘Black Sunday’ About?

Set and filmed in Moldavia, Black Sunday starts with the execution of Princess Asa Vajda (Barbara Steele) and her lover, Javutich, who are accused of witchcraft. Asa’s vow of revenge turns into a curse, which resurfaces several centuries later, when two men of science, Dr. Kruvajan (Andrea Checchi) and his assistant, Andrej (John Richardson), stumble upon the princess’ tomb, and Kruvajan’s blood accidentally brings her back to life. After resurrecting Javutich as well, Asa sends him on the hunt for the remaining members of the Vajda’s family, including Katia, who is the princess’ new physical reincarnation and a spitting image of her. As Asa gets ahold of Katia and drains her of her youth to regain her life force, it’s up to her brother and Andrej, who had managed to promptly fall in love with Katia, to save her.

When Bava first got the go-ahead from an Italian studio, Galatea, to proceed with his debut, he felt inspired to make something not too dissimilar to Terence Fisher‘s version of Dracula (1958), which was a huge cinematic sensation at the time. As a literary source for the story, Bava, who also worked on the script, first set out to adapt Nikolai Gogol‘s classic folk horror story, Viy, which was yet to gain its iconic screen version at the time. The screenplay was later reworked as a much looser rendition of Gogol’s story, also cementing one of Bava’s future distinctive features—a glorious ambivalence towards the intricacies of literal storytelling in favor of the cinematic one. Combining visual creativity with musical splendor, Bava not only built his own recognizable style here, but also led the way for the generations of his colleagues engaged in the making of the tradition fittingly nicknamed “horror operas.”

‘Black Sunday’ Is Both Stunningly Beautiful and Decadently Gruesome — Setting the Tone for the Bright Future of Italian Horror

In just a span of several years, Bava laid the ground for two major traditions in Italian genre cinema. While his The Girl Who Knew Too Much (1963) and especially his macabre visual masterpiece, Blood and Black Lace (1964), started a wave of bloody and inventive Giallo mysteries, Black Sunday opened a chapter in Italian cinema dedicated to Gothic horror—yet, a version different from its American and British counterparts. While Bava will be known for his incredible work with color in his films, which will also become a distinctive feature of Italian horror, especially its Giallo tradition, his first film comes in black and white. However, even without a vivid color palette at his disposal, Bava doesn’t resort to copying American genre patterns, reaching instead for the great tradition of Italian art, drawing inspiration in its use of deep shadows, symbolic imagery, and optical illusions that also have the power to create a surreal reality on screen.

Bava makes a woman the central figure of his macabre tale in Black Sunday, not satisfied with the classic patriarchal Gothic stories and their usual monsters. Italian horror will soon follow his example, quickly becoming obsessed with witches, female demons, and murderous seductresses, but also interesting and self-sufficient female protagonists of all kinds. In his directorial debut, Bava gives us both sides—the future iconic Scream Queen, Barbara Steele, plays the dual role of a vampiric witch princess who rises from the dead for revenge and her innocent contemporary reincarnation. The duality is also present in the film’s aesthetics and atmosphere, where the exquisite beauty and the graphic, gruesome cruelty (such as stabbing through the eyes, which would become a staple in Italian horror) can coexist, sometimes within the bounds of the same scene.

Unapologetic onscreen violence would also become a distinctive feature of Italian horror and in other traditions inspired by it, such as classic slashers. In Bava’s film, it also serves a thematic purpose, as it represents the duality of human nature, which can be both appalled and fascinated by evil, as evident in the story of Asa, who isn’t shown as an outright monster but as a tragic figure, cruelly punished for being the victim of seduction and manipulation herself. Drawing inspiration from another forgotten tradition of Italian cinema, the Diva films, German expressionism, and the surreal works of Jean Cocteau, Bava is also prone to turning his stories into dark fairytales. In Black Sunday, the concept of true love as a viable weapon against evil forces is introduced but depicted as something that is inherent to the cruelty and unfairness of the world, since not everyone is lucky enough to obtain it. Thus, the last and most crucial duality in Bava’s debut and future films comes not from his ability to create fantastical visions but from his talent for depicting our familiar reality as full of secrets, wonder, and inviting darkness.

Black Sunday

- Release Date

-

August 11, 1960

- Runtime

-

86 minutes

- Director

-

Mario Bava

-

Barbara Steele

Princess Asa Vajda / Katia Vajda

-

John Richardson

Dr. Andrej Gorobec / Dr. Andreas Gorobec

-

Andrea Checchi

Dr. Choma Kruvajan / Dr. Thomas Kruvajan

-

[ad_2]